|

| "The Postman", Mesopotamia 1919 |

Some entries ago I

talked about the Central Power mission in Afghanistan in 1915-1916. I have

found more information about it, and it has resulted to be an incredible

adventure. What a fascinating place was Afghanistan in those years!

The Niedermayer-Hentig

Expedition was a diplomatic mission to Afghanistan sent by the Central Powers

in 1915 with the purpose to encourage Afghanistan to declare full independence

from the British Empire, enter the Great War on the side of the Central Powers

and attack India; none less.

This was a joint

operation of Germany and Turkey nominally headed by the exiled Indian prince

Raja Mahendra Pratap but lead, really, by the German Army officers Oskar

Niedermayer and Werner Otto von Hentig.

To Great Britain, it

was a serious threat, and unsuccessfully attempted to intercept the expedition

in Persia during the summer of 1915. Britain also waged a covert intelligence

and diplomatic offensive in Kabul, including personal interventions by the

Viceroy Lord Hardinge and King George V, in order to maintain Afghan

neutrality. Fortunately for them, the mission failed in its main task of

rallying Afghanistan, then under Amir Habibullah Khan, to the Central Powers

war effort, but it was able to influence other major events in the country. The

expedition triggered reforms and drove political turmoil that culminated in the

assassination of the Amir in 1919 and the Third Afghan War. It also influenced

the Kalmyk Project (it will have another entry) of the Bolshevik Russia to

propagate socialist revolution in Asia.

|

| The Niedermayer-Hentig Expedition in Kabul, 1916. From left to right: Kazim Bey, Werner Otto von Hentig, Walter Röhr, Mahendra Pratap, Kurt Wagner, Oskar Niedermayer, Günter Voigt and Maulavi Barkatullah |

Background.

In response to the

war with Russia and Great Britain, and motivated by its alliance with Turkey,

Germany accelerated a plan to weaken its enemies by targeting their colonial

empires, including Russia in Turkestan and Britain in India, using as its

weapon political agitation.

Germany began this

plan by nurturing its prewar links with India nationalists, who had used Germany

as their base for anti-colonial work against Great Britain. This effort was led

by a prominent archaeologist and historian, Max von Oppenheim, who headed the

Intelligence Bureau for the East and formed the Berlin Committee, later

re-named as the Indian Independence Committee. The Berlin Committee began offering

money, arms and military advisors to Indian revolutionaries, hoping to trigger

a nationalist rebellion using clandestine shipments of men and arms sent to

India. From the late XIX Century, von Oppenhein had mapped Turkey and Persia

while working as a secret agent, when Germany began to contemplate efforts to

threaten India through Turkey, Persia and Afghanistan.

Once at war, Turkey

joined Germany in the aim to opposing Entente Powers and their empires in the

Muslim world. Enver Pasha had the Sultan proclaim the jihad, with the hope to provoke and aid a vast Muslim revolution,

particularly,in India. However, while widely heard, the proclamation did not

have the intended effect of mobilizing global Muslim opinion on behalf of

Turkey or the Central Powers.

Early in the war, the

Amir of Afghanistan had declared neutrality of his country, and he feared that

the Sultan´s call to jihad would have

a destabilizing influence on his subjects. The moment was very delicate for

him, because Britain controlled Afghanistan´s foreign policy and the Amir

himself received a monetary subsidy from Britain. On the other hand, the

British perceived Afghanistan to be the only state capable of invading India. In fact, a German General

Staff memoranda in the last weeks of August 1914 confirmed the previously

perceived feasibility of a plan to use the pan-Islamic movement to destabilize

the British Empire and begin the Indian revolution, predicting that an invasion

by Afghanistan could cause a revolution in India, where revolutionary unrest

had increased with the outbreak of war.

The First Expedition.

When the pan-Islamic

movement in India made plans for an insurrection in the North-West Frontier

Province, with support from Afghanistan and the Central Powers, proposing that

the Afghan Amir declared war against Britain, Enver Pasha conceived

quickly an expedition to Afghanistan in 1914 as a pan-Islamic venture directed by

Turkey, with some German participation. An escort of nearly a thousand Turkish

troops and German advisers would to accompany the delegation through Persia

into Afghanistan, where they hoped to raise local tribes to jihad.

All of this was a

curious fiasco. The German participants attempted to reach Turkey by travelling

through Austria-Hungary in the guise of a travelling circus, but their

equipment, arms and mobile radios were confiscated in the neutral Rumania when

there were discovered the wireless aerials sticking out through the packaging

of the tent poles… Then, differences between

Turkish and German officers, including the reluctance of the Germans to accept

Turkish control and wear Turkish Army uniforms, further compromised the effort

and, eventually, the expedition was aborted.

The Second Expedition.

In 1915, a second

expedition was organized, mainly through the German Foreign Office and the

Berlin Committee, and the exiled Indian prince Raja Mahendra Pratap was named

its leader. He was head of the Indian princely states of Mursan and Hathras and in

1912 had contributed substantial funds to Gandhi´s South African movement.

Pratap left India at the beginning of the war and was convinced by the Berlin

Committee to lend his support to the Indian nationalist cause. In a private

audience with the Kaiser, Pratap agreed to nominally head the expedition,

chosing six Hindu Afridi and Pathan volunteers from the prisioners of war camp

at Zossen as his personal retinue.

Prominent among the

German members of the delegation were Niedermayer and von Hentig. Von Hentig

was a Prussian military officer fluent in Persian, former secretary of the

German legation to Tehran in 1913, that was serving on the Eastern Front as a

lieutenant with the Prussian 3rd Cuirassiers. Niedermayer had served

in Constantinople before the war and also spoke fluent Persian and other

regional languages. He was a Bavarian artillery officer that had returned to

Persia to await further orders after the first expedition was aborted.

He was tasked with the military aspects of this new expedition as it travelled

through the dangerous Persian desert between British and Russian areas of

influence.

So, the titular head

of the expedition was Mahendra Pratap, while von Hentig was the Kaiser´s

representative, responsible for the German diplomatic effort to the Emir. To

fund the mission, 100,000 pounds sterling in gold was deposited in the Deutsche

Bank in Constantinople and the expedition was also provided with gold and other

gifts for the Emir, including jeweled watches, gold fountain pens, ornamental

rifles, binoculars, cameras, cinema projectors and an alarm clock.

Reaching

Constantinople on 17 April 1915, Pratap and von Hentig met with Enver Pasha and

enjoyed an audience with the Sultan, adding a Turkish officer, Kasim Bey, as

the Turkish representative.

The group, numbering

around twenty people, left Constantinople in early May 1915 and crossed the Bosphorus,

travelling over the Taurus Mountains on horseback and using the same route taken

by Alexander the Great. The group crossed the Euphrates at high flood and

reached, finally, Baghdad towards the end of May.

On 1 June the party

left Baghdad to make their way towards the Persian border. Persia at the time

was divided into British and Russian spheres of influence, with a neutral zone

in between in which Germany exercised influence through their consulate in

Isfahan. The local populace and clergy, opposed to Russian and British colonial

designs on Persia, offered support to the mission but details of its progress were being keenly sought by British intelligence, and British

and Russian columns close to the border with Afghanistan, including the Seistan

Force, were looking for the expedition, so it would have to outwit and outrun

its pursuers over thousands of miles in the Persian desert, while evading

brigands and ambushes.

|

| Mahendra Pratap and Kazim Bey, disguised, in Mesopotamia, 1915 |

With camels and water bags purchased, the different parties of the expedition left Isfahan separately on 3 July 1915 for the travel through the desert, expecting to rendezvous at Tebber, halfway to the Afghan border. The group of von Hentig crossed the Persian desert in forty nights (really appropiate!) and reached Tebbes on 23 July, soon followed by Niedermayer´s party which now included the explorer Wilhelm Paschen and six Austrian-Hungarian soldiers who had escaped from a Russian POW´s camp in Turkestan.

Still 200 miles from the Afghan border, the expedition now had to treat with the British patrols of the East Persia Cordon (Seistan Force) and also with Russian patrols. Niedermayer sent two patrols to draw away the Russian and British troops and a third one, of thirty armed Persians led by a German officer, to scout the route. Menavhile, the main body headed through Chehar Deh for the region of Birjand, close to the Afghan frontier.

|

| Seistan Force´s patrol near Gusht in 1916 |

The first patrol was destroyed by the Russian, but Nierdermayer was able to proceed towards Birjand, in forced marches, fighting all the way with the opium adiction of the Persian camel drivers. With a Russian consulate in Birjand, Niedermayer decided to bypass the town by the harsh northern route. By the second week of August, the expedition was close to the Birjand-Meshed road, eighty miles from Afghanistan, at last.

|

| Map of the Sistan border with Afghanistan, by Colonel Reginald Dyer, commander of the Force |

Finally, on 19 August 1915, the expedition reached the Afghan frontier with approximately fifty men, less than half the original number who had set out from Isfahan seven weeks earlier. Only 70 of the 170 horses and pack animals survived and many of the bulkier and heavier gifts of the Kaiser to the Emir had been buried in the desert for later retrieval.

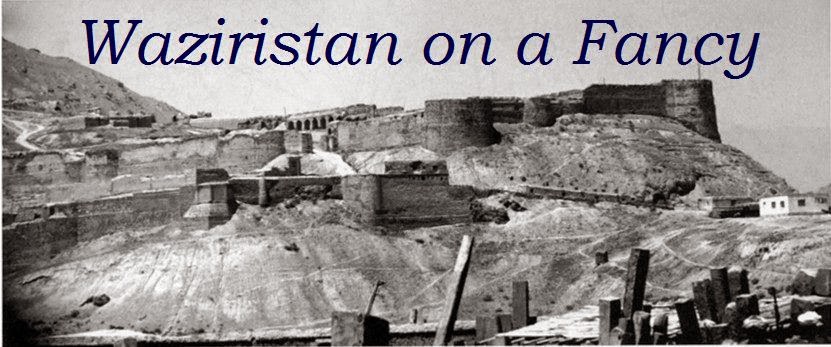

|

| Herat Citadel |

In Afghanistan, the group found fresh water in an irrigation channel (teeming with leeches) that saved them from dying of thirst. Two days later, they reached the vicinity of Herat, where they made contact with Afghan authorities. Von Hentig sent Barkatullah, an Islamis scholar, to advise the governor that they had arrived with a Kaiser´s message and gifts for the Amir. The governor sent a grand welcome with noblemen, servants and an escort, inviting the expedition into the city as guests of the Afghan government, on 24 August. In an official meeting with the governor, von Hentig showed him the Turkish Sultan´s proclamation of jihad and the Kaiser´s promise to recognise Afghan sovereignty and German assistance. The Kaiser also promised to grant territory to Afghanistan as far north as Samarkand, in Russian Turkestan, and as far into India as Bombay.

The governor promised to arrange for the 400 miles trip east to Kabul, in two weeks, time that the expedition used to make themselves presentable for the meeting with the Amir. On 7 September, the group left Herat for Kabul via the harsher northern route through Hazarajat. Finally, on 2 October 1915, the expedition reached Kabul and was received with a salaam from the local Turkish community and a guard of honour from Afghan troops "in Turkish uniform".

At Kabul, the group was accommodated as state guests at the Amir´s palace at Bagh-e Babur, where it was soon clear for all of them that they were all but confined, with armed guards around the palace and armed guides on their journeys. For three weeks, Amir Habibullah responded with only polite replies to request for an audience. He was an astute politician, and was not in a hurry to receive his guests. Only after a threaten of a hunger strike for the part of von Hentig and Niedermayer, began the meetings.

Habibullah was an eccentric lord of Afghanistan, owned of the only newspaper, the only drug store and all the automobiles in the country (all Rolls Royces, of course). His brother, Prime Minister Nasrullah Khan, was, on the other hand, a man of religious convictions. Unlike the Amir, he fluently spoke Pashto (the local language), dressed in traditional Afghan robes and interacted closely with the border tribes. While the Amir favoured British India, Nasrullah Khan was more pro-German, and his views were shared by his nephew, Amanullah Khan, the youngest and most charismatic of the Amir´s sons. The mission, therefore, expected more sympathy and consideration from Nasrullah and Amanullah than from the Amir...

|

| Habibullah Khan |

On 26 October 1915, the Amir finally granted an audience at his palace at Paghman. The meeting lasted the entire day and began with Habibullah expressing surprise that a task as important as the expedition was entrusted to such young men, regarded by him as mechants. Von Hentig had to convince him that the mission did not considered themselves merchants, but emissaries from the Kaiser, the Ottoman Sultan and India whising to recognise Afghanistan´s complete independence and sovereignty. Passing along the Kaiser´s invitation to join the war on the side of the Central Powers, von Hentig described a favourable war situation and invited the Amir to declare independence. Then, Kasim Bey explained the Ottoman Sultan´s declaration of jihad and Barkatullah invited Habibullah to declare war against the British Empire and to come to the aid of India´s Muslims, proposing than the Amir should allow Turco-German forces to cross Afghanistan for a campaing towards the Indian frontier. He and Mahendra Pratap, both eloquent speakers, pointed out the rich territorial gains the Amir stood to adquire by joining the Central Powers.

The Amir´s reply was really shrewd but frank. He noted Afghanistan´s vulnerable position between Russian and Britain, and the difficulties of any Turco-German assistance, given the presence of the Anglo-Russian East Persian Cordon. He was also financially vulnerable, dependent on British subsides and institutions for his fortune and the welfare of his kingdom and army (very important, this point). Merely tasked to entreat the Amir to join a holy war, the mission did not have the authority to promise anything, so they could not answer his questions about strategic assistance, arms and funds.

This conference was followed by an eight-hour meeting in October 1915 at Paghman, and other audiences at Kabul, but all of them had the same message. These meetings tipically began with Habibullah describing his daily routine, followed by words from von Hentig on politic and history. Next came discussions about Afghanistan´s position on the propositions of allowing Central Powers troops the right of passage, the breaking with Britain and the declaration of independence. The Amir sought concrete proofs that the Turco-German assurances of military and financial assistance were feasible in such a way that Walter Röhr later wrote to the Prince Henry of Reuss in Tehran that a thousand Turkish troops headed by himself (of course) should be able to draw Afghanistan into the war.

Meanwhile, the mission found a more sympathetic and ready audience in the Amir´s brother, Nasrullah Khan and the Amir´s younger son, Amanullah Khan. In secret meetings, this party encouraged the mission, giving them reasons to feel confident. Rumour of these meetings reached Habibullah, passed on by the British and Russian intelligence. These rumours suggested that, to draw Afghanistan into the war, von Hentig was prepared to organize "internal revulsions" if necessary. Habibullah found these reports concerning, and discouraged expedition members from meeting with his sons except in his presence. In fact, all of Afghanistan´s immediate preceding rulers save Habibullah´s father had died of "unnatural" causes, so he was justifiable fearing for his safety and his kingdom.

|

| Nasrullah Khan |

During the months that the expedition remained in Kabul, Habibullah fended off pressure to commit to the Central Powers war effort, waiting for the outcome of the war to be predictable, announcing to the mission his sympathy for the Central Powers and asserting his willingness to lead an army into India... with Turco-German troops in it. Meanvhile, the members of the expedition were allowed to freely venture into Kabul, a liberty that they used to put on a successful "hearts and minds" campaing spending freely on local goods and paying cash. Two dozen of Austrian prisoners of war who had escaped from Russian camps were recruited by Niedermayer to construct an hospital and Kasim Bey met with the local Turkish community, spreading Enver Pasha´s message of unity and Pan-Turanian jihad.

Habidullah also tolerated the increased ant-British and pro-Central tone taken by his newspaper, Siraj al Akhbar, whose editor was his father-in-law, Mahmud Tarzi. Tarzi published a number of very incendiary articles by Mahendra Pratap that, in May 1916, were considered serious enough for the Raj to intercept the copies intended for India.

|

| Four of the Pathan volunteers with Walter Röhr in Landespolizei uniform near Kabul, 1915 |

Political events, including the foundation of the Provisional Government of India, and their own progress allowed the mission, during December 1915, to celebrate at Kabul on Christmas Day with wine and cognac left behind by the Durand mission forty years previously.

Mahendra Pratap was procalimed president and Barkatullah Prime Minister of this Provisional Government and support was obtained from Galib Pasha for proclaiming jihad against Britain. After the February Revolution in Russia in 1917, Pratap´s government began to correspondent with the nascent Bolshevik government in an attempt to gain their support.

In the same month of December, the Amir told von Hentig that he was ready to discuss a treatry of Afghan-German friendship. On 25 December 1915, a final draft of ten articles was presented, including clauses recognising Afghan independence, a declaration of friendship with Germany and the establisment of diplomatic relations. The treatry would also guarantee German assistance against Russia and Britain if Afghanistan joined the war on the Central side. The Amir´s army was to be modernised with 100,000 modern rifles, 300 artillery pieces and other warfare equipment provided by Germany. The German must maintain advisors and engineers, and an overland supply route through Persia for arms and ammunition. Finally, the Amir would be paid 1,000,000 sterling pounds.

Von Hentig and Niedermayer signed this document, considered by them as an initial basis to prepare for an Afghan invasion of India. Niedermayer was so confident that asked for 20,000 German troops to protect the Russian-Afghan frontier and informed the general staff to expect the campaing to begin in April.

It was great news for the Central Powers, but, in the end, Habibullah returned quickly to his vacillating (and cunning) inactivity. He know the mission had found support whiting his council and had excited his volatile subjects so, four days after the signing of the draft treatry, Habibullah called for a durbar. Instead of calling a jihad, he reaffirmed his neutrality arguing that the war´s outcome was still umpredictable. Throughout the spring of 1916, he continuosly deflected the mission´s overtures and increased the stakes, demanding that India rise in revolution prior of his own campaing.

Habibullah had received, in the meantime, British intelligence reports that said he was in danger of being assassinated but, at the same monet, his tribesmen were unhappy at Habibullah´s perceived subservience to the British and his council and relatives openly suspected his inactivity.

In that delicate moment, the war took a turn for the worse for the Central Powers that save Habibullah´s position. The Arab revolt ended the hope to send a Turkish division to Afghanistan and the German influence in Persia declined rapidly, ending the hopes that Goltz Pasha could lead a Persian volunteer division into Afghanistan. Finally, the mission came to realise that the Amir deeply mistrusted them. A last offer was made by Nasrullah in May 1916 to remove Habibullah from power and lead the frontier tribes against the British, but von Hentig knew it would come to nothing, and the German decided to left Kabul on 21 May 1916.

They knew that once they were out of the Amir´s lands, the Anglo-Russian forces and the marauding tribes of Persia would chase them mercilessly so the party split in several groups to make their way back to Germany.

Having served previously in Pekin, von Hentig escaped over the Hindu Kush and made his way on foot and horseback through Chinese Turkestan over the Gobi Desert and through China and Shangai. Via the USA, he finally reached Berlin on 9 June 1917.

Niedermayer escaped towards Persia through Russian Turkestan. Robbed and left for dead, he finally reached friendly lines, arriving in Tehran on 20 July 1916.

Mahendra Pratap attempted to seek an alliance with Tzar Nicolas II from February 1916 without result, but was able to correspond more closely with Lenin´s Bolshevilk government. In 1918, he suggested to Trosky a joint German-Russian invasion of the Indian frontiers, recommending a similar and only Bolshevik plan to Lenin in 1919.

Epilogue.

This curious and adventurer expedition really disturbed Russian and British influence in Central Asia, but it was, probably, some years premature in its political objectives, taking in account Habibullah mind. On the other hand, the expedition planted the seeds of sovereignty and reforms in Afghanistan. Habibullah´s neutrality alienated a substantial proportion of his family members and council advisors, and fed discontent among his subjects. He was finally assassinated while on a hunting trip in 1919, two weeks after his demands of complete sovereignty and independence were rebuffed by the Viceroy. The Afghan crow passed first to Nasrullah Khan and then to Amanullah Khan, the most intelligent of his sons. Both of them had been staunch supported of the expedition.

The Third Afghan War was precipitated by all these events and, after a number of brief skirmishes, it was signed the Anglo-Afghan Treatry of 1919, in which Britain, finally, recognised Afghan independence. Amanullah proclaimed himself King and Germany was one of the first countries to recognise the independence of his government.

Throughout the next decade, Amanullah Khan instituted a number of social and constitutional reforms which had first been advocated by that extraordinary group of adventurers, the Niedermayer-Hentig Expedition.